As the eight sector studies illustrate, people’s livelihoods in each sector are affected by digitization and platformization in different ways. We draw from our framework to highlight some cross-cutting lessons on how platformization and digitization are impacting the livelihoods of young Kenyans and offer some reflections on platform livelihoods in general, particularly as they relate to diversity and inclusion, and takeaways for policy and design.

Reflections on the diversity of platform livelihoods

Young people’s experiences vary from sector to sector.

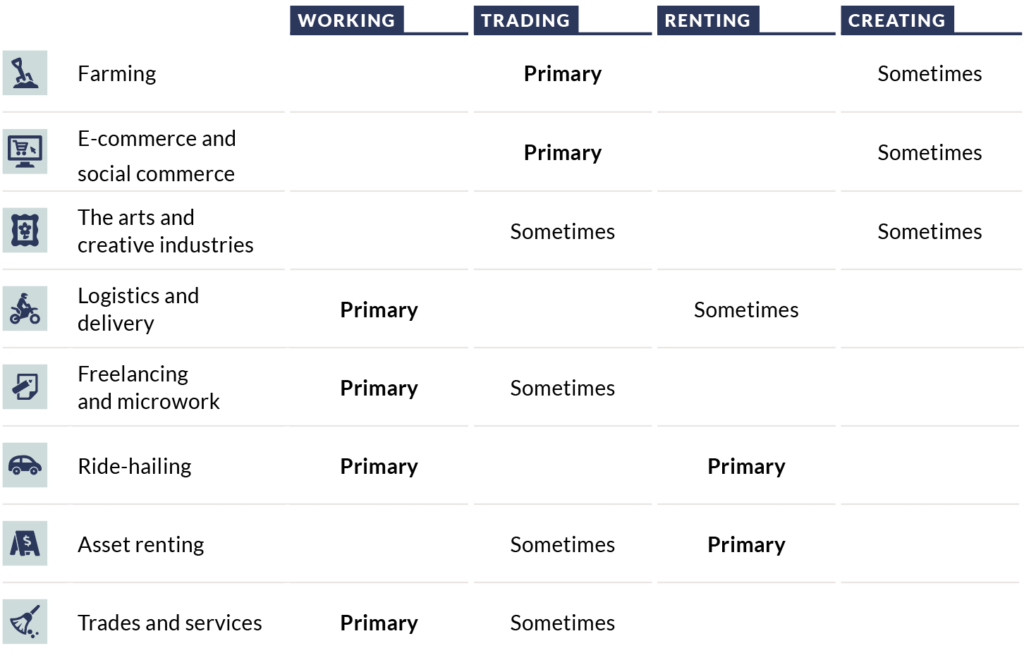

There are four elemental ways in which people can earn a livelihood on a platform: by working, by trading, by renting, by creating, or often through a combination of these ways.

- Platform working: Delivery logistics, local services, ride-hailing, and freelancing are commonly recognized as “gig work” or platform work, as are, sometimes, the trades and services. In each case, independent contractors access day-to-day income opportunities through dedicated marketplace apps or informal social media marketing in ways that often resemble a “job” or “employment” but without much of the security a job provides

- Platform trading: Among MSEs, there are different approaches between those who had established retail brick-and-mortar locations and those who began digital-only selling, often during the pandemic. The latter depend on marketplace platforms (or hyper-local delivery apps) as their exclusive channel. Regardless, individuals acting as MSEs were less likely than those in gig work to feel like the algorithm was defining their lives and acting like a boss. The farmers interviewed are likely not representative of all Kenyan farmers. They were relatively well-educated, relatively urban, and remarkably excited about how these same kinds of channels, be they formal marketplaces or, particularly, social media, help them thrive in upmarket agricultural ventures. Where freelancers, artists, and people in trades and services are selling their services or productions to multiple clients via platforms, they, too, are engaged in trading.

- Platform renting: Interviewees included people who rented homes/rooms, as well as audio equipment. Popular narratives may focus on a person who owns an asset and shares it for extra money on the side, or even as a primary source of income. Some interviewees, “asset owners,” pursued this kind of livelihood. But in many cases, individuals first rent an asset from an (actual) asset owner and then re-rent the asset via platforms to make money. This process involves thinner margins and a more precarious position.

- Platform creating: The artists we spoke to are, in many respects, a unique or edge case, but their experiences with digital platforms are quite instructive given the extraordinary nature of the creative process. Like platform workers, visual artists and musicians offer products or services; thus creative workers also have to figure out how to work with algorithms on both domestic and international platforms to survive. Others are better described as what the industry has begun to call “creators”—those who make digital content for consumption online or, especially, to drive engagement and advertising impressions. From influencers to musicians, this work is captivating and high-profile, even if it still is relatively rare, and even if actual returns remain scarce for all but the occasional breakout star.

Elements of platform livelihoods across eight sectors

Workers and sellers use platforms in many ways: sometimes fractionally, sometimes in combination.

This study revealed how varied and combinatorial platform practices are. This is partly because platforms are so varied. It is not always the case that people only need to learn how to use one platform well, or that one platform can serve as the exclusive gateway or channel for that person’s labor or sales. Instead, people need to find a broad set of digital capabilities in order to engage with multiple platforms in unique ways.

Similarly, interviews demonstrated evidence for the idea, encountered in the literature review, that people are often fractional users of any given platform. Perhaps this is particularly the case in Kenya, where “side hustles” are commonplace.

There are no solid boundaries between casual employment, self-employment, and entrepreneurship.

Interviewing people in a variety of sectors showed how the distinctions between work, self-employment, and entrepreneurship are often quite blurry. It is a common frame in the “gig work” discussion that gig work is just employment, without the safety, security, and social benefits of a contract. In some cases, particularly logistics, this characterization was largely accurate. On the other extreme, some farmers and MSEs were clearly entrepreneurs. They ran a business, paid employees, and only turned to one or more platforms as a new channel—a new source for inputs or a channel through which to attract and serve customers.

Social is a widespread practice with unique risks.

For some individuals, “social” (WhatsApp and Facebook, especially) may be the first and only ways in which they engage in digitally mediated working, trading, sharing or creating. For others, these practices will involve a mix of informal and formal, unstructured and structured, social and purpose-built platforms.

Social commerce is an unregulated, rough-and-tumble space. Fraudsters, scams, sexual harassment, and missed connections abound, and there is little recourse for those who wish to do business with strangers via the soup of the advertising-driven newsfeed or in moderated WhatsApp and Facebook groups. These risks are real problems that need to be addressed and solved.

Platform workers and sellers assess the quality of their experiences more broadly than on income alone.

Income matters, first and foremost. After that, it is a border range of factors (flexibility, security, entrepreneurial chances, opportunities to learn and grow, etc) which individuals may come to value in combinations as different as the people and the livelihoods themselves.

“I think besides the money that we seek, we also seek customer satisfaction. There are some clients I work for. Not because they’re paying me well, or they’re not paying me well. I work for not because I like, I actually like them. It’s like a family thing. Like for example, the school kids they take to school the family like depends on you and you feel like, I have to.”

Reflections on inclusion

Youth

By design, almost all interviewees were young. With minimal barriers to entry, many youth are turning to platforms for earnings against a backdrop of high unemployment and a scarcity of full-time jobs. Many of the emerging entrepreneurs, however, reported challenges in lacking resources (mostly financial) to upskill and grow their businesses. Conversely, enthusiasm, openness to change, and relative levels of comfort with digital technologies were apparent across all sectors. Clearly, the further intertwining of platform livelihoods in the Kenyan economy will most closely involve the young.

Rurality

In thinking about platform livelihoods in rural areas, it is helpful to distinguish between “placeless” work, like freelancing and microtasking, that can be performed anywhere there is an internet connection, and “geographically tethered models” that depend on local clients, and/or local logistics infrastructure, to support transactions.

Digital platforms are not a cure-all for problems facing rural Kenyans. Quite simply many of the local models (ride hailing, logistics, local services, etc.) require a sufficient density of local customers to make the geography worthwhile for platforms to cover. For the time being, digital innovation and the cultivation of platform practices—with the exception of farming—are still mostly urban, and mostly for younger people who are more tech-savvy.

Gender

At least half of interviewees from each sector were women, with the exception of logistics and ride-hailing, in which women are still underrepresented. This study design may have only begun to unpack and address the challenges and opportunities that platform livelihoods present for women. The interview samples may show survivorship bias; by only speaking to relatively successful female drivers, artists, shopkeepers, farmers, etc., the barriers to platform livelihoods that particularly affect women are not discussed. Participants described some of the long-standing dynamics of gender in each of the eight sectors. Issues of sexism, navigating the assumptions of “this is a man’s job” (or this is a woman’s job) and a need to adopt a stereotypical male attitude towards being a business owner were raised.

In late 2021, we conducted a multi-country follow-up study specifically on gender to expand on these themes, applying an expansive lens on women’s empowerment to this newer area of platform livelihoods.

"[There is] A little bit of male chauvinism around. I won’t lie. There is a lot of sexism that is around. But there is also the advantage of the fact that you are a woman that people will easily believe you or trust in you. You know? So you look at it in both ways. It’s an advantage sometimes and sometimes a disadvantage."

Disability

The research team also sought out people with disabilities involved in each sector. Some mentioned being able to participate equally, despite various limitations: “with online, people first judge you by your work, not how you look.” Some sectors are, however, limited based on the nature of the work. Gig workers with disabilities mentioned the need for additional resources to be able to participate and earn via the platforms. In 2022, Caribou Digital and inABLE are conducting a follow-up study on disability and platform livelihoods in Kenya.

COVID-19

Of course, this research was completed during the COVID-19 pandemic. One-on-one interviews were conducted while masked in well-ventilated rooms; eventually, the research team shifted to remote interviews. The disruption of COVID-19 in the middle of 2020 involved both a health and economic crisis, exposing the vulnerabilities in platform livelihoods and simultaneously cementing the role of platforms, showing increased digital transformation. As discussed in the sector studies and in another storytelling project, platform workers and sellers experienced different paths during the crisis.

“COVID happened and I had a lineup of exhibitions—all of them were canceled. I think that is when the internet came through because now clearly you are not going anywhere and the only way to show your work is through the internet. I feel like it was an eye-opener ‘cause now you are able to market yourself on social media.”

A path forward

This study documents what is happening with digital platforms in Kenya. It is another task to focus on questions of what should be happening—how to make platform livelihoods work well for all Kenyans. The breadth of the youth experiences portrayed in this study makes it less likely that there are one-size-fits-all policy responses or design interventions that would make all platform livelihoods more dignified and fulfilling for more youth, in Kenya or elsewhere in Africa.

The main takeaway for policymakers and others who want to engage with digital transformation for inclusion and advancement is more likely that each sector may need close attention and a tailored response.

Equating “digital platforms” with gig work, and regulating and designing for them as such, may not serve many others relying on platforms for livelihoods in other ways: self-employed sellers (formal or social), asset renters, and content creators.

Other recommendations include:

- Avoid focusing exclusively on individuals. Our research shows how there are “hidden hierarchies” and opportunities for employment beyond profile holders, such as those who do maintenance on the rental home or make the food that gets sold by the restaurant to a delivery app. There are more people involved in the platform economy than are initially apparent.

- Fractional work is pervasive. There certainly are full-time “gig workers.” But since not everyone depends on a single platform for all their income, nor are platforms entirely responsible for the quality of every working person’s livelihood, interventions may have to work systemically rather than on a per-platform basis.

- Look for ways to help youth with onboarding and showcasing. Marketplace platforms and social media sites place the onus for promotion on individual workers and sellers. Yet initially, gigs and ratings are so hard to get, and the risks of a bad rating so extensive, that established and better-resourced individuals have a leg-up on newcomers.

- Take social seriously as a way to include youth into the digital economy. Social has emerged as an informal, diffuse alternative to the fees and rigid structures of formal marketplaces. There’s not just social commerce—there is social ride-hailing, social gig work, social trade work, social sharing, even social agriculture. In addition to ratings and reviews, interventions on training, fraud projection, payment integration, and o marketing can each make social platforms more effective and useful as livelihood platforms for youth.

- Consider how platform livelihoods work for women. Notably, flexibility, though valued by many, takes on different characteristics for women, many of whom see that “flexibility” became expectations that they be both online earning AND available for caregiving. In 2022 Caribou Digital, Qhala, and several other partners have conducted a follow-on study on this topic, and other gender-related challenges to effective participation in platform marketplaces in Kenya, Nigeria, and Ghana.

- All of these livelihoods—whether working or trading, renting or creating—are challenging, and the path to success is far from guaranteed. Many youth interviewees spoke about precarity and the struggle to achieve scale, either in the volume and value of their earnings as workers, or in the growth of their enterprises as entrepreneurs. Partly because these livelihoods are flexible and fractional, partly because they often offer access to larger and more efficient markets, and partly because the platforms themselves claim a share of revenues, prosperity and growth of individual workers and sellers can be difficult to achieve.

Key next steps for future research

- Research to better understand the percentage of Kenya’s workforce that is platformitized, particularly using methods that could account for hidden hierarchies, multi-homing (using two or more platforms at once), and fractional work.

- Research to document the pathways in and out of platform livelihoods. These trajectories will be key in assessing the quality of platform livelihoods relative to alternatives and as elements of a person’s lifetime progression of work.

- Studies that complement the qualitative approaches used to assess platform livelihood experiences with quantitative approaches to assess worker and seller earnings relative to their peers who are not using platforms, and relative to prior employment.

In one respect, this study is the intermediate point in a four-part series. We started with a literature review which identified twelve distinct elements of the quality of experience of platform work, nine distinct sectors, and a variety of platform practices. This study uses that framework to present the experiences of eight of these sectors. Looking ahead, we will further explore the complexities of gender in platform work, explore the emerging practice of social agriculture, and explore how platform livelihoods are (or are not) accessible and rewarding for people living with disabilities.

On one hand, Kenya should look to conversations happening around the world about regulatory interventions to improve social protections and the social contract between gig workers and platforms. On the other hand, Kenya needs to evaluate its own particular stance towards each of these platform livelihoods, in order to develop the solutions that make the most sense for Kenya. Regardless, this work helps demonstrate how there is likely not a one-size-fits-all approach to catalyzing the platform economy.

Despite ups and downs in the funding environment, business models, and the evolution of the pandemic, the advance towards the digital economy will likely continue. It is the right moment to work together to make platform livelihoods—a key new part of digital transformation—inclusive, dignified, and fulfilling for more youths in Kenya and beyond.

Explore the different sector reports

The arts and creative industries: Digital channels as a source of inspiration, distribution, and a platform to educate audiences on the value of art.

Asset renting: People can earn a living by renting out assets they own (like property, tractors, or specialized equipment) or by renting them then re-renting them out in smaller fractions.

Delivery and logistics: Fast-paced work, driven by algorithms. Structured weekly earnings, support in bookkeeping, budgeting, and saving.

E-commerce and social commerce: Experiences with platform sales via formal marketplaces, social commerce, paid and free online advertising.

Farming: Formal multi-sided marketplaces built to connect farmers to markets and “social agriculture,” the practice of using social media to sell agricultural commodities and get social support in communities.

Freelancing and microwork: To connect with clients all over the world for everything from data processing to graphic design and writing, freelancers must build a personal brand while microworkers mostly remain anonymous.

Ride-hailing: In big cities and smaller towns, ride-hailing is a mix of working and asset renting, as the driver and their vehicle are intertwined.

Trades and services: Domestic and care work, trades for custom-made products, and a myriad of other services, delivered on demand and matched by marketplaces and social media.

This platform livelihoods research was conducted by Qhala in collaboration with Caribou Digital and in partnership with the Mastercard Foundation.